- The anti-essentialist model presents nature as differently experienced according to one’s social position and is differently produced by different groups across different time periods. The framework identifies and conceptualizes 3 distinct nature regimes–organic, capitalist, and techno–and sketches their characteristics and imperfections (Escobar 1999).

- The political implications of the anti-essentialist framework are discussed in terms of the strategies of hybrid natures that most social groups seem to be faced with as they encounter particular manifestations of the environmental crisis (Escobar 1999).

- “Use, not logic, conditions belief.”

- “Cultural models of nature are constituted by ensembles of meanings/uses that, while existing in contexts of power that increasingly include trans-national forces, can neither be reduced to modern constructions nor be accounted for without some reference to grounds, boundaries, and local cultures. Documentation of these ensembles of meanings/uses should be situated in larger contexts of power and articulation with other nature regimes and global forces.”

Escobar, A. (1999). Steps to an antiessentialist political ecology. Current Anthropology, 40(1), 1-30.

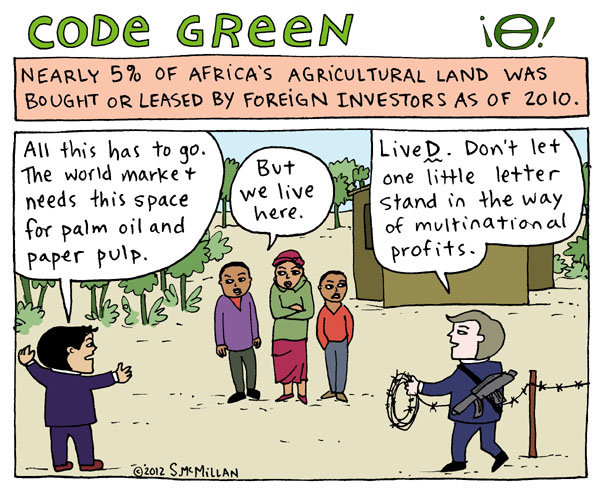

- Escobar argues we are in a “crisis of nature,” including a crisis of nature’s identity. The constant shift of cultural, socioeconomic, and political factors have caused the meaning of nature to change over time, claiming that cultural and biological resources for collectively “inventing” natures and their identities are unevenly distributed. This is a common theme across much of the literature in review, presented in slight different ways. Essentially, the cultural and political hegemonic influence creates great disparities between the distribution of cultural and biological resources on a global level. Anti-essentialist ideas about nature identity concern the fact that identities are continuously and deferentially created and sustained; partly in the context of power. The anti-essentialist notion calls for a “plurality of natures,” one in which both biological and social natures play central roles. Escobar argues that there are three landscape regimes in tension with one another; capitalist, organic, and technocratic landscapes. The capitalist landscape deals with production and modernity, focusing on rational, expert knowledge to manage resources. In this landscape, it is important to note the ways in which nature have been “governmentalized,” in which nature becomes embedded in the economy. The organic landscape, on the other hand, is defined by the notion that nature and society cannot be separated, they are intertwined. The organic landscape is seen in many “3rd world” societies, in which nature cannot be manipulated, and local models of nature can be seen as links between the biophysical, human, and supernatural domain. There is no unified view on what constitutes a local model of nature, but several features are often seen, including: they reveal a more complex image of the natural and social world being integral to one another, attachment to territories are multidimensional interactions, and that rituals are often central to interactions between human and natural worlds. Emphasis is placed on the fact that local environmental knowledge must be seen in set of context-specific improvisional capacities rather than constituting a complete knowledge system. A central argument to implementing organic views of the environment is that although it greatly differs from modern models of environmental use, economics, and production, local models exist chiefly in practice. The technonature landscape encompasses modern day artificial technologies. Escobar notes here that the invention of real-time technologies demonstrates the global delocalization of human activity, calling to explore how local cultural and material resources in marginalized communities are used to mobilize an adaption or hybridization of their identities. Hybridization is a mechanism used by “3rd world,” indigenous communities to incorporate multiple constructions of nature (the local and the global) simultaneously to negotiate with external forces while maintaining some form of cultural cohesion. The anti-essentialist view in my opinion is extremely important to global environmental management within the future. Ample research and case studies are available illustrating the multidimensional and multi-faceted nature of human-environmental relations and should be examined within the same realm, not separated.

*See abstract filing cabinet for further information